Fly People

First week impressions at the wet lab | Warning: slightly gross

None of us were Fly People1,

and none of us will be.

We came because the flies are clones2 of us

to understand ourselves through infinite generations of them.

I never intended to kill them!

I just wanted to know how creatures make their bodies.3

Yet 1000 flies died in this room each week.

Then another 10004 flies were born each week.

I even felt like a mother,

I even fed them apple juice.

They wouldn’t have lived long in the wild.

I also felt like a farmer:

We are so proud to extract data from their skin and guts,

so excited to learn what life is from their dying.

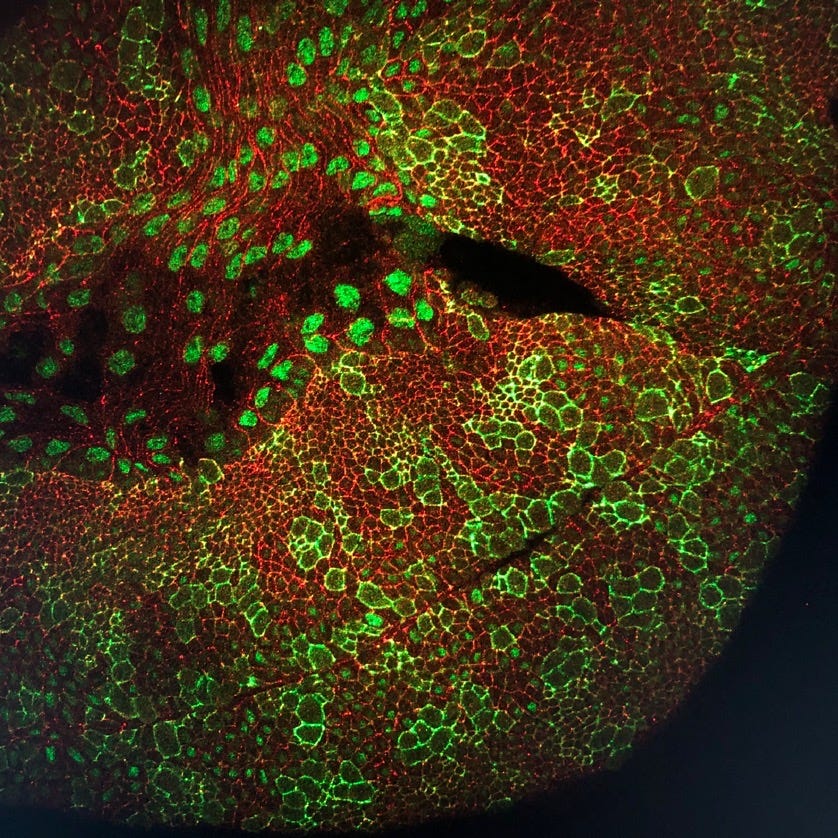

What if someone were to soak me in bleach, then ethanol, then boil5,

plate me under a laser microscope,

make a beautiful image of my fragments glowing in green and magenta antibodies,

just to learn how cells move?

Before I joined this lab, I thought humans who don’t code went extinct.6

My lab exists to mock me.

“Why spend hours finding virgins?

Why not just train a neural network?”

“That would take more time.”

“Why memorize the location and schedule of 100 bottles, each containing a different messed up mutant, stacked on unmarked shelves?

Why not just write them on a kanban? “

“You know where your mutants are by muscle memory.”

Perhaps I, too, can survive without keeping everything on the internet.7

But it won’t be easier

to keep what you heard in your heart

to copy what you saw with your hands

to sync your day to the lifecycle of embryos.8

I won’t be alone;

I’m with the 100 years9 worth of humans that live for fruit flies.

Fly People: A nickname for the researchers who study Drosophila (AKA fruit fly). On my first day at the lab, I was struck by my labmate’s comment that “the fly community is the most collaborative community [she has] ever been in.” Since the field is ancient yet not well-quantified, and the data only stays on living flies, researchers must mail flies around.

Model system: fruit fly is a species used to study generalizable properties. For example, humans and flies share some similar proteins. We could make vague inferences about humans if we understand how that protein works in flies by tweaking the protein and seeing its effects. This is why many lab members (to my comfort) never worked with flies before. We all came for the basic questions that can be answered through this animal.

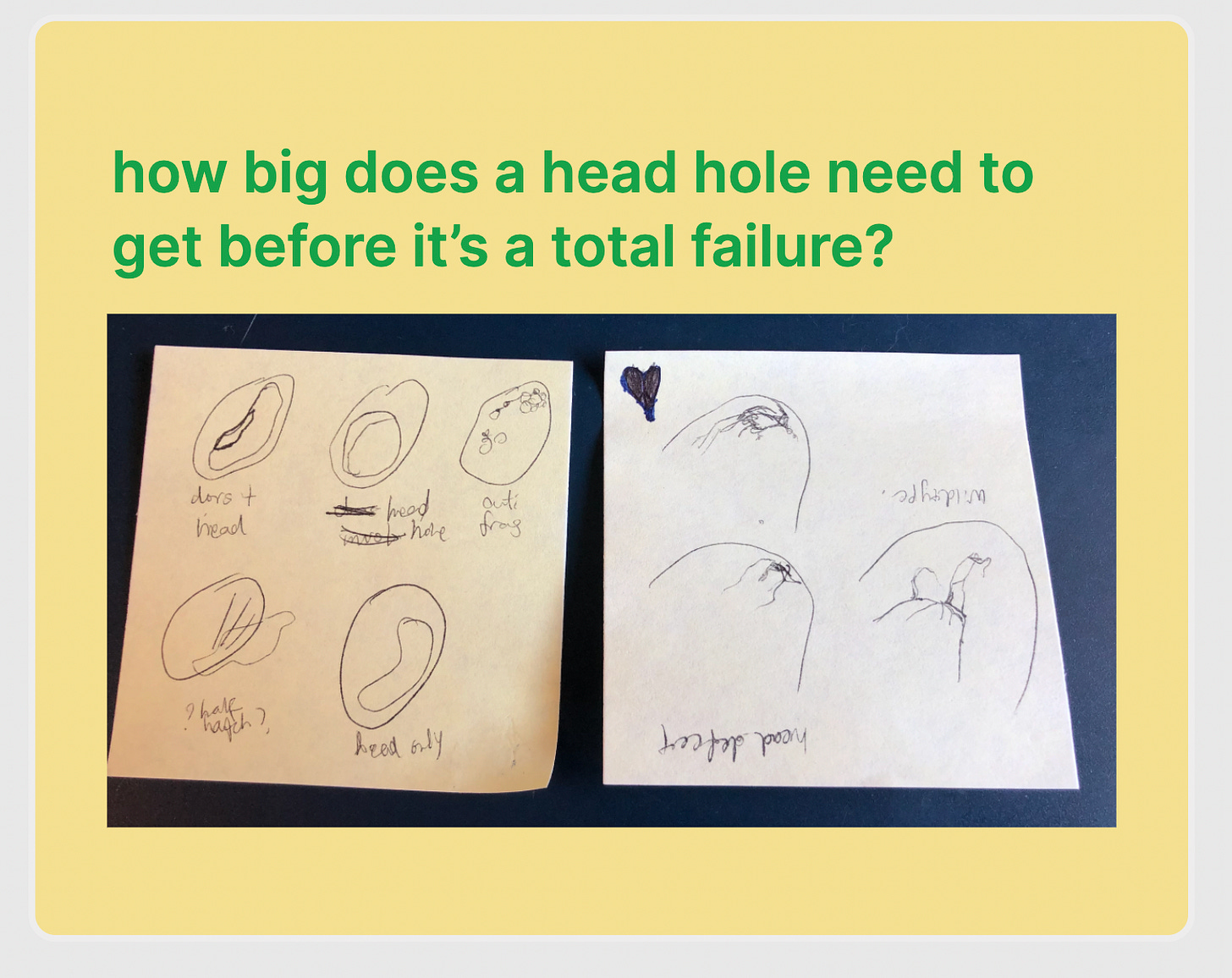

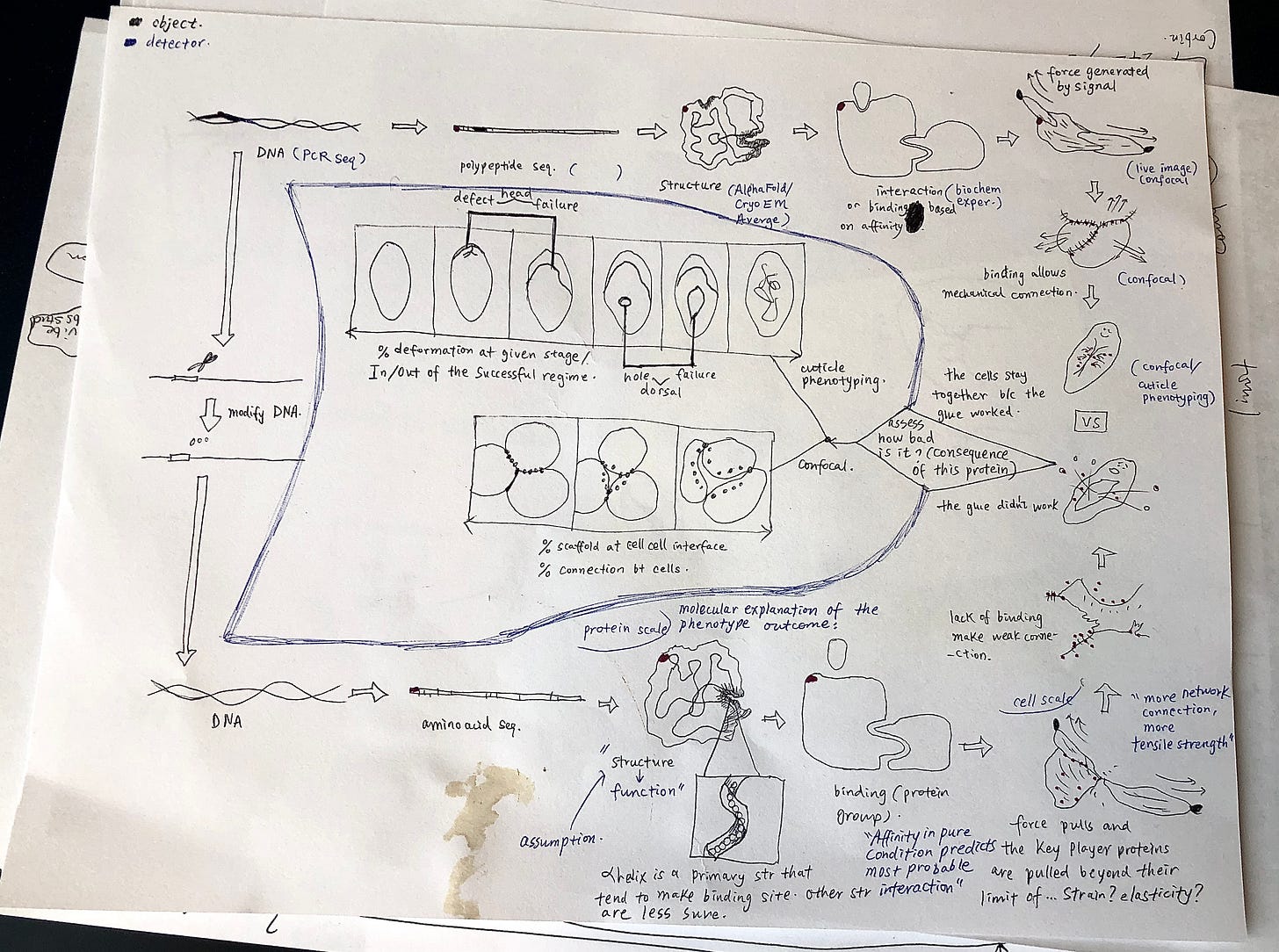

Morphogenesis: How does a tiny cell fold into a complex body with organs like the gut, eyes, and nervous system? Imagine a network of proteins as the midwives of this transformation. They need to connect a cell's inner framework (cytoskeleton) to the glue (adherens) that holds cells together. If the framework pulls cells apart, the glue must keep them intact. A mistake in timing or location could create a hole in the skin, spilling guts everywehre. How do these proteins work together, especially when some parts seem structureless and hard to connect? This is the puzzle we’re filling.

Estimation: This is my estimate, to which my labmate said “probably”. I have been throwing around unfounded estimations to retain my quantitative brain cells. Experimental biology is a foreign language to me because it relies on images, large sample variations, and qualitative network explanations.

Heat shock: We want to see the proteins in the inner sheet of cells lining the egg. To do so, we need to perform a heat shock procedure, where we bleach the outer exoskeleton that prevents light from the microscope to go through, then heat and organically condense the second layer, and finally stain the proteins in the cell sheet with antibodies from rabbits and chickens to make the proteins light up (fluoresce) when we shoot lasers at the embryo (that is now sitting still because it’s way dead).

Physicality: In college I didn’t have a physical lab, I worked with simulations as my experiments, I used computers and at most notebooks for all my notes and planning, I mainly learned and solved concepts around the physical laws or mathematical entities or computational structures. Here it’s the reverse: everything is either in the lab or in people’s memory, experiments are done on live animals that generate the data through a long lifecycle process that relies on the functioning of many machines and people and animals, we mainly deal with concepts around the puzzle of a specific region of the cell and its probabilistic causal relations through very observable diversity of their hints.

Notetaking: A key difference between this lab and my college is where memory is stored — in the heart or on the internet. “Don’t take notes, you will forget everything I say and that’s ok, as you do the things and listen to these words over and over you will gradually understand.” In contrast, all summer and throughout college I had been influenced by classmates interested in the online community of productivity tools, tools for thought, note-taking and knowledge management systems, workflows for research and writing, habits of mind and mental models, methods for thinking better and faster. I had been learning to synthesise my understanding through writing. How might I reconcile the difference in dominant approaches?

Metabolism and Temperature: I was intrigued that we plan our morning and afternoon workday around the flies’ age. How long a fly lives depends mostly on temperature. A fly lives roughly 18 days under 18 degrees Celsius and 8 days under 25 degrees Celsius. This is because when the temperature is lower, the flies' enzymes adjust to lower their speed of chemical reactions, slowing metabolism — an adaptation evolved over eons. In fact, everything becomes slower — the flies also spend a longer time in childhood when they can’t mate. Virgins carry the genotype we want so that we can mate virgins with the boys from the other genotype. The first and last thing we do at the lab is to find virgins.

History: In 1910, a guy in the US realized how easy it is to mutate fruit flies. Fruit flies probably lived with humans for longer than that. The history and people side of Drosophila research intrigued me. I perked my ear up whenever my labmates mentioned snippets, and I indulged in the introduction of the books <Fly Pushing> and <Atlas of Drosophila>. I was surprised that the fruit flies spread worldwide, mainly through labs and lab-related providers. Companies sell them. China has factories that CRISPER the flies cheaper than a postbac like me. When I say they spread, they are not contained in the labs: many genetically engineered mutants fly out just from my week of sorting flies.