When pastures shift from collective to private

感生6. Conversation with Sang Mo's father at Shangrire pasture

For July 11-12 I went with Langmuzhuoma to her family at Shangrire village and pasture, near Huahu wetlands in the Sichuan province area of the Tibetan plateau.

On July 12th the entire clan went to celebrate དབྱར་སྟོན། (Yarden), the village summer festival, which featured dancing, singing, horse racing, beauty contests, dress-up games, ant games, and meetings between village leaders.

Last month, Shangrire and Xiarire villages finally transitioned from collective pastures to individual family plots, and they've begun building fences. This festival was the first time the two villages held it together, as they worried that dividing the pastures might create distance between people.

During the festival, I mostly hang out with Langmuzhuoma’s 11 year-old niece Sang Mo and her cousins.

We picked wolfsbane flowers for Sang Mo's mother, who was making momo dumplings in the kitchen tent, to make flower crowns for us.

We also played the traditional plant identification game together - all the little monks, girls, mothers, uncles, and grandfathers participated. It was intense: each group went out for 10 minutes to collect plants, then returned to spread them on the red cloth of monk robes, holding up plants to see if other groups had them, debating whether two types of leaves were the same species.

We had three or five races that day, running wildly over dried cow dung patties, pika holes and small hills, and various flowers and grasses. Running and shouting on the grassland felt really comfortable. After running, everyone collapsed in the tent, panting heavily.

While resting in the tent between the dance performances and dinner, Langmuzhuoma helped me translate and chat with her uncle, Sangmo’s father, who is a herder around 40 years old.

Sangmo's father learned herding at age 10, following his second uncle (his much older brother, the dark-faced one, the most skilled and diligent herder). Sangmo’s father herded both sheep and cattle but never horses.

In the past, herders needed to walk animals to grazing areas in the morning and stay with them all day before bringing them back in the afternoon. Now, with convenient transportation, they generally drive the animals to grazing areas in the morning, leave the herd there to graze, then return in the afternoon to bring them home. This change to driving happened over ten years ago when living conditions improved. When living conditions improved, thefts became rarer. Herders can relax, visiting teahouses, resting, or playing basketball during the day before collecting animals in the afternoon.

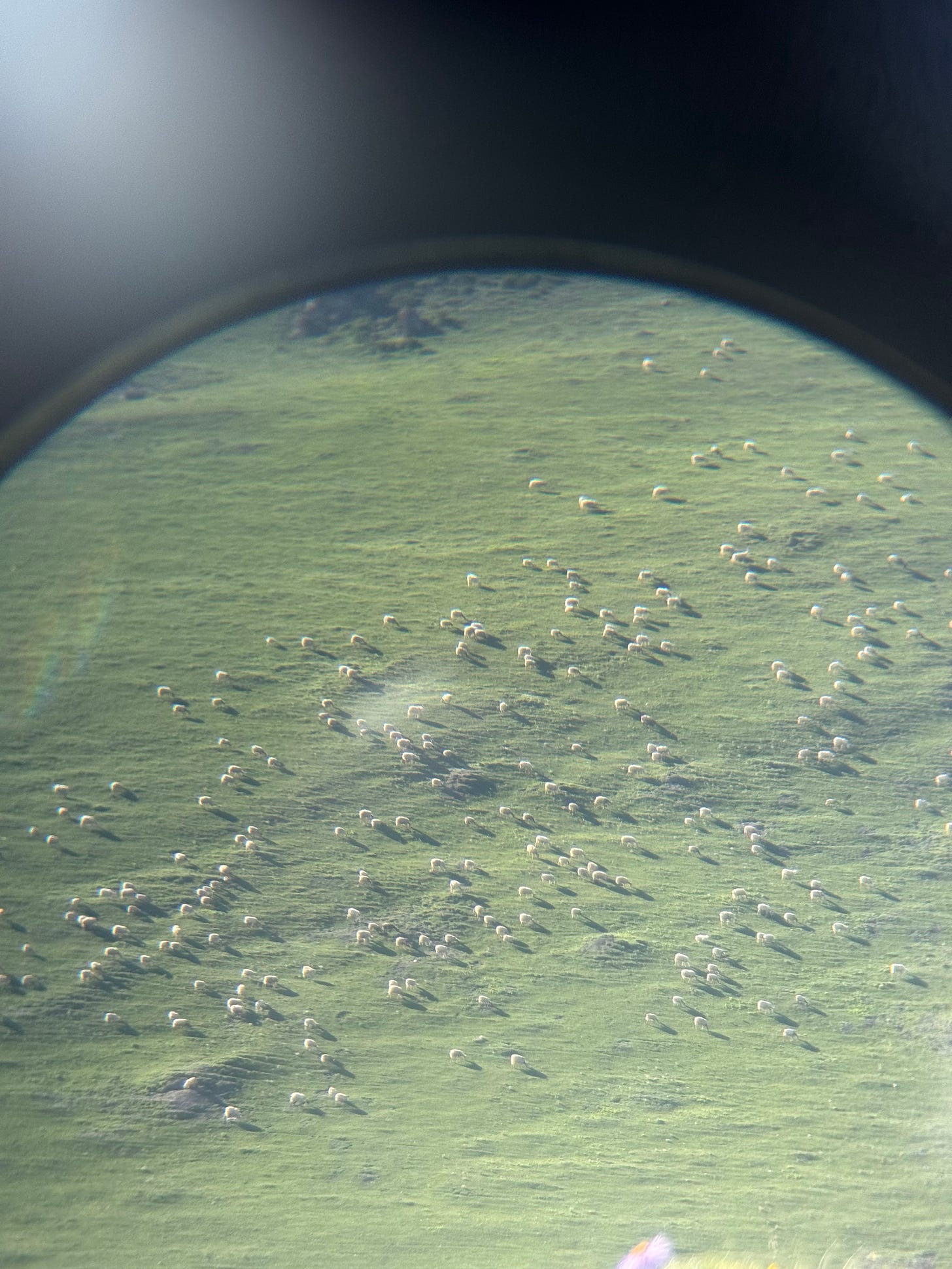

Herders choose grazing locations based on good grass and water, driving animals there to slowly spread out and graze. Winter grazing happens on plains, while summer pastures are in the mountains - there's no choice if pastures are in mountainous areas. They divided pastures because when grazing together, different families' sheep and cattle would mix, requiring manual separation. With divided pastures and fences, each household eliminates this separation work and reduces labor from moving between pastures.

Cattle herds do have leadership and social structure, though Langmuzhuoma couldn't translate the professional term for it. Some cattle are more diligent or selective, leading others in eating.

The grassland has deteriorated since his childhood - more (pika and groundhog) holes and bare patches have appeared. Cattle and sheep numbers have increased, and while pikas are the primary cause of grass deterioration, increased livestock also plays a role. When pikas dig holes and rain fills them, the drying process causes greater grassland destruction. The holes themselves greatly impact grass, separating grass roots that can't fuse back together.

Under collective ownership, individuals wouldn't fill holes since the land wasn't theirs, even though conditions were poor. Now with divided pastures belonging to families for 30 years or permanently, people invest effort in blocking holes and gradually repairing them, having hope for their pastures. With personal ownership comes personal protection of grassland, since families depend on grass to raise livestock.

Sangmo’s father has two older sons who both entered the monastery, and three younger children, who each stayed for a while with their aunt in Chengdu for school. The younger children mostly live with their grandparents when the parents stay at the pasture. For his children's future, Sangmo’s father hopes they continue studying and accomplish something outside. He'd be very supportive of that. But if they can't study well or have various problems preventing them from establishing themselves in society, he'd still hope they return to use herding as their main livelihood.

I am currently staying with Langmuzhuoma because I wanted to learn about how yaks shape grassland, how pastoralists can stay on the grassland. I was grateful that Zhuoma helped me translate for her family. It is much better than if I immediately started asking people interrogating questions without any relationship-building process. It felt good to spend days just getting along, playing, chatting, eating, preparing food. It feels more like friendliness.