fieldwork context

In late May, I visited Tangtou Village in Zhejiang Province to perform ecological survey. The work was organized by Shanshui Conservation Center, an NGO focused on biodiversity and local community collaboration. This site near Qianjiangyuan (a proposed national park) is a pilot for integrating biodiversity monitoring with rice and tea farming.

ecological monitoring

Our main task was maintaining infrared camera traps placed at key points in rice paddies and forest edges. Camera traps are motion-triggered devices that automatically capture photos or videos of wildlife. They're useful for monitoring shy or nocturnal animals without needing a person to be present. We checked the traps, replaced batteries and memory cards, and adjusted their angles. Some traps had been knocked off target by cows grazing in the fields overnight.

The goal of this setup was to record species presence, activity patterns, and potential differences in biodiversity between fields that use chemical pesticides and fertilizers and those that don’t. These paired plots, one conventional, one low-chemical, were part of a pilot experiment to assess how ecological farming impacts wild animal presence.

In addition to camera traps, we also joined bird and amphibian surveys. The bird surveys happened early in the morning, when volunteers stood at sample sites near rivers and fields, listening and spotting birds by sound or sight. At night, we looked for amphibians like frogs and toads in the wet margins of rice paddies. Amphibians are sensitive to chemicals and habitat changes, making them useful indicators for environmental monitoring.

One of the sites where we worked was higher up the mountain. There, the trap had captured images of 5 porcupines moving in a group. Another camera, placed at a crossing point between forest ridges, recorded several sightings of a small deer species.

talking to local farmers

We met villagers while adjusting the cameras or passing through the fields. Many stopped to ask what we were doing. One elderly farmer, seeing us setting up near his rice paddy, asked if we were installing fire alarms. Another farmer, hard of hearing, assumed we were construction workers there to open a new highway. These moments of confusion often led to longer conversations.

A retired Chinese teacher farmed next to the crested ibis conservation area. In 2021, the endangered species were reared in the cage then re-wilded in their original habitat. The teacher said that the conservation staff bought and put loaches into the fields because there was not enough food for the ibis. As we walked back, he pointed out the local crops mainly for eating: corn, taro, oil tea, tea, pepper, french beans, plums, eggplants, cabbages, potatos.

Several farmers we met were concerned about the visible decline in frogs and tadpoles. One auntie told us, “tadpoles die every year en masse,” attributing the disappearance to chemical use. A farmer near the mountain explained that they used to burn crop residues (stems, leaves, and weeds) as a way to create ash-based natural fertilizer. He added that people had been moved down from the hills to reduce fire risk, and that government patrols now respond quickly to any sign of smoke.

land policies and local implementation

One of the background policies at play is the use of conservation easements (地役权) in the region. Farmers receive subsidies in exchange for not using pesticides and chemical fertilizers, and only planting subsistence crops like rice instead of commercial crops like tea.

Additionally, only large-scale farmers or cooperatives can negotiate with the government for this ecological subsidy, because the central government prefers easier management. The large entities increasingly leased land from individual households.

The ban on burning crop residues is another point of tension. The traditional method of using ash as a natural fertilizer was cheap and effective for many households. One local farmer told us: “bunds and irrigation channels and the lack of fuel serve as natural firebreaks, even if I take a nap the fire will not cross to the forest.”

However, national regulations since the late 1980s have enforced strict bans on open burning during designated fire prevention seasons. After a catastrophic forest fire in Daxing’anling in 1987, laws like the 1993 nationwide prohibition of straw burning and the updated 2015 Air Pollution Control Law were implemented, mandating fines and even criminal charges for violations. These rules apply regardless of local geography or traditional practices.

While prescribed burning is allowed under special conditions in forest areas, it is almost never permitted for agricultural land. Farmers in Tangtou expressed frustration that their knowledge of controlled burning was dismissed. They felt the bans were overly generalized, disconnected from the low-risk reality of their terraced paddies, and failed to consider the role of ash in soil fertility. One also described how quickly the fire brigade arrives now if any smoke is seen—reflecting high surveillance levels in the region.

The local ecosystem includes forest edges, terraced rice fields, irrigation ditches, and mixed-use hillsides. These areas support amphibians, small mammals, birds, and reptiles. Some species only appear when water is available or crops are present, complicating efforts to define what counts as “farmland biodiversity.” Volunteers noted that even common species like frogs or sparrows were indicators of pesticide use or habitat change. Meanwhile, forest health is also a concern, as pine trees in the area have been widely affected by a disease (松材线虫病), prompting government-controlled burns to prevent spread.

The villagers we spoke with seemed most focused on how these policies affect income and land use. Some found the restrictions burdensome or the compensation insufficient. Others were curious but not opposed. I noticed that most decisions about how to manage land or apply restrictions still feel top-down, even when participatory language is used.

personal emotions

One night we were out for a casual amphibian survey. Many colleagues were keen to chase rare birds or snakes. In my voice diary that night I said, "maybe right now I'm feeling a bit sleepy, and what I really want to do is just stand in the paddies and listen to the frogs and sense and maybe sing."

That night I played songs from Zhuang tribe and Miao tribe on my phone. I heard these songs from Yunnan in 2023. The sound moved me in a different way now. I wrote, "it's not exactly the same as when they were singing and playing it right there in Yunnan... maybe it's the audio or maybe it's just a different place." I felt deeply, a kind of still emotion I couldn’t name, something that comes from standing in a place long enough to let it touch you.

Overall, I also noticed differences in how people related to the fieldwork. Some volunteers were knowledgeable about many species, but particularly focused on rare species. I found myself more drawn to questions about how farming practices and ecological goals interact, and how knowledge is shared or excluded. I want to keep learning from both directions: scientific method and local experience.

what’s next

I am reaching out to Shanshui’s academic collaborators and see if there is a way to support or extend this work through data analysis. I’m also thinking about the broader questions raised: What kinds of practices truly support coexistence between farming and biodiversity? How can local people lead or shape conservation goals? How do national policies translate into daily decisions?

唐头村

五月底,我前往浙江省的唐头村,参与一项生态调查工作。该项目由“山水自然保护中心”组织,该机构致力于生物多样性保护与本地社区协作。唐头村靠近拟设立的钱江源国家公园,是一个以水稻和茶叶农业为基础的生态监测试点地区。

我希望了解农田如何支持野生动物,以及农民、科学家、志愿者与政府工作人员之间如何在这个交界点互动。

生态监测

调整红外相机、读取拍摄数据

我们的主要任务是维护安装在稻田和森林边缘的红外相机。红外相机是一种运动触发设备,可自动拍摄野生动物的照片或视频,特别适合监测害羞或夜行性动物,无需人员时刻在场。我们检查相机、替换电池和内存卡,并调整拍摄角度。有些相机因牛在夜间放养被撞偏了方向。

这个监测设置的目的是记录物种的出现、活动模式,并对比使用农药/化肥与不使用农药/化肥的农田之间生物多样性的差异。这些成对设置的地块(一块常规耕作,一块低投入生态耕作)是一个试验项目的一部分,旨在评估生态农业对野生动物的影响。

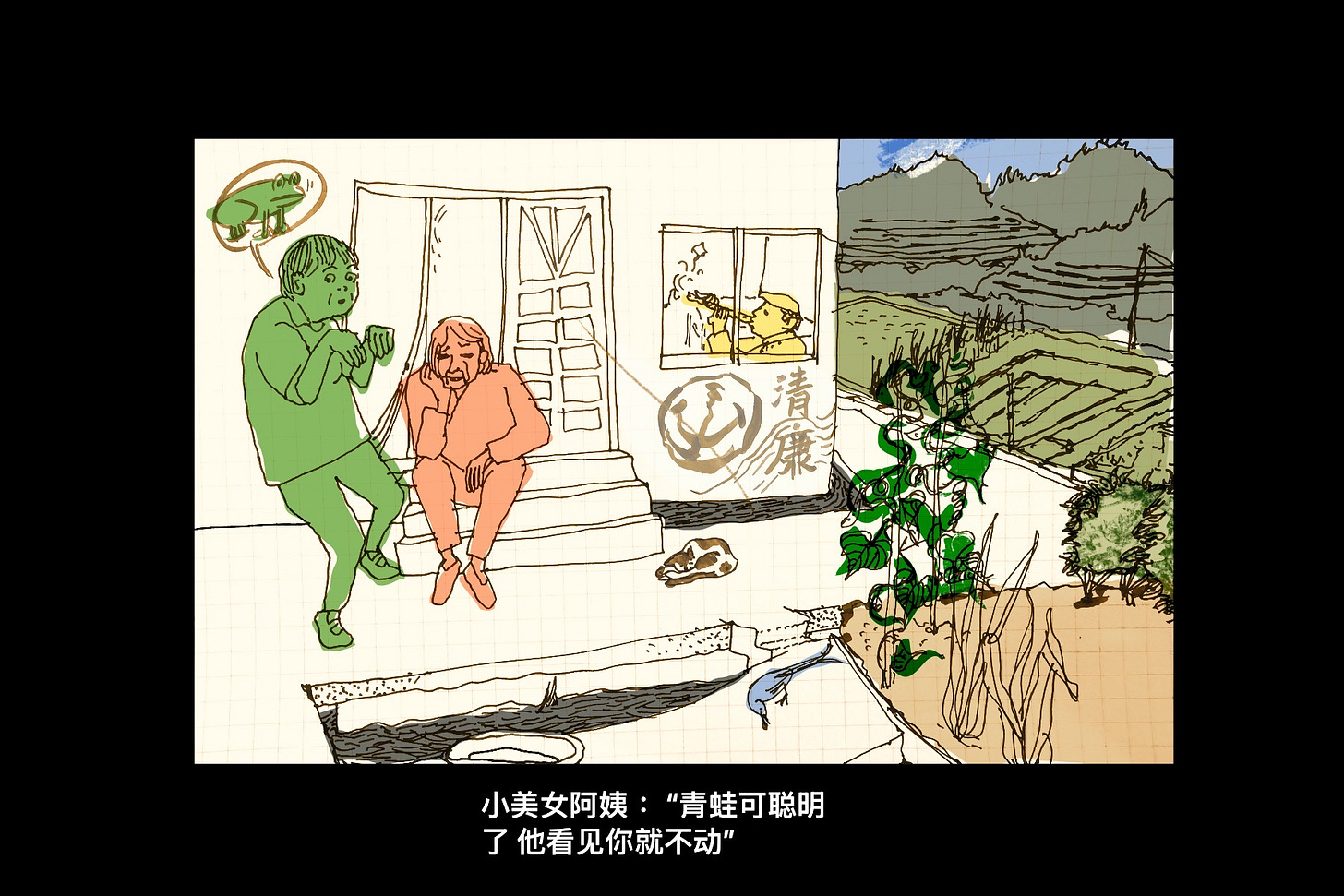

图1 左:家明的观鸟镜头;中:永睿模拟雉鸡的高度;右:小杨搬着修理红外相机的工具

除了红外相机监测,我们还参与了鸟类和两栖动物的调查。鸟类调查在清晨进行,志愿者在靠近河流和田边的采样点定点观察,通过声音或目视记录鸟类种类。夜晚则寻找蛙类等两栖动物,主要集中在稻田湿润的边缘区域。由于两栖动物对化学品和栖息地变化非常敏感,因此是生态环境变化的良好指示物种。

图2 我们把调查中见到的一些动物用“八大山人”风格重新画了下来。

我们工作的一处点位在山上较高处。那里的一台红外相机拍到了五只成群结队的豪猪。另一台安装在森林山脊交汇处的相机则多次拍到了小麂的活动。

与农民交谈

图3 一位阿姨模仿“看到人就一动不动”的聪明青蛙,引来大家大笑。

我们在调整相机或经过农田时经常与村民交流。很多人会停下问我们在干什么。一位大爷看到我们在稻田边架设设备,问我们是不是装火警的。另一位听力不好的大爷以为我们是来修高速公路的施工队。这些误会往往成为更深入对话的起点。

一位退休语文老师现在在朱鹮保护区旁边继续务农。他告诉我们,这些珍稀鸟类在2021年被圈养繁殖后重新放归自然。他说因为朱鹮食物不足,工作人员特意向稻田里投放了泥鳅。我们一起走回村庄时,他边走边指出附近种的农作物,基本上是自给自足型:玉米、芋头、油茶、茶树、辣椒、四季豆、李子、茄子、卷心菜、土豆。

很多农民都提到青蛙和蝌蚪明显减少。一位阿姨说:“蝌蚪年年都死光了”,她认为是因为农药使用。一位山边的农民告诉我们,以前农民会烧秸秆、杂草和落叶,做成灰肥。他补充说,近年来村民被搬离山上是为了减少火灾风险,现在只要冒一点烟,政府的消防队就会立即出现。

土地政策与地方执行

图4 1776年的石碑,刻有禁砍树和偷油的规则,被用作中国古代“禁伐护林”传统的证据。

该地区的重要背景政策之一是“地役权”制度。农民可以通过签署协议获取生态补偿,但前提是不能使用农药化肥,只能种植像水稻这样的口粮作物,不能种茶这类经济作物。

此外,只有规模化种植户或合作社才有资格和政府协商补贴事宜,因为中央政府倾向于统一管理。这些大户逐步从村民手中租赁土地,成为新的决策中心。

焚烧秸秆的禁令是另一个焦点议题。用灰肥施田是便宜有效的传统做法。一位农民说:“田埂、水渠、没有燃料,本来就是天然的防火带,我睡个午觉都不会烧过去。”

然而自1980年代末以来,国家在特定防火期内实施了严格的禁烧政策。1987年大兴安岭特大森林火灾后,1993年出台了全国范围的秸秆焚烧禁令,2015年修订的《大气污染防治法》更是对违规者处以罚款乃至刑责,不论地方地形和传统。

虽然“规定性焚烧”在森林管理中被有限地允许,但在农田中几乎不会获批。唐头村的农民对此表示无奈,他们认为自己的经验和安全操作被忽视。这些禁令太“一刀切”,脱离他们田间操作的实际,而且没有考虑灰肥对土壤肥力的重要性。有位村民说:“现在一冒烟,警报响,消防车就来了。”他认为这是过度监控的体现。

唐头村的生态系统包括林地边缘、梯田水稻田、水渠及混合利用的山坡地。这些区域支撑着蛙类、小型哺乳动物、鸟类和爬行动物等多种野生物种。有些动物只有在灌溉或农作物生长期才会出现,使得“农田生物多样性”的边界更为复杂。志愿者指出,即便是青蛙、麻雀等常见物种,也能反映出农药使用和栖息地质量的变化。同时,山上的松树普遍感染了松材线虫病,政府正在组织控制性焚烧。

我们交流的村民最关心的是这些政策如何影响他们的收入和土地安排。一些人觉得政策有负担或补贴不足,也有人表示观望和好奇。我发现多数土地管理决策仍然是自上而下,即使用“参与式管理”的语言来包装。

个体感受

图5 emo时刻的鸡皮疙瘩

某天晚上,我们进行两栖动物调查。很多同伴都兴奋地寻找稀有鸟类或蛇类。而我在语音日记中说:“我其实有点困,我现在只想站在田里听青蛙叫,感受一下,也许唱一首歌。”

那晚我播放的是壮族和苗族的歌曲,我在2023年云南时听过现场演唱。这次在田野里听却是另一种感受。我写道:“和她们在云南现场唱时听到的不一样了……也许是录音的问题,也许是地方变了。”那是一种很难命名的静态情感,是那种“你在一个地方站得够久,它才开始触动你”的感觉。

图6 徐老师(钱江源国家公园工作人员)还说,南方的蟑螂“大得像小鸟”,我们都笑了。

我还注意到,不同人参与生态工作的方式差异很大。有些志愿者认识很多物种,特别是对珍稀物种很感兴趣。我自己则更关注农业实践与生态目标之间的互动,以及知识如何在田间被传播或排除。我希望继续从两个方向学习:科学方法和地方经验。

下一步

图7 农田灌溉渠

我正在联系山水中心的学术合作方,希望能通过数据分析进一步参与这个项目。同时,我也在思考更广泛的问题:什么样的实践才能真正支持农业与生物多样性的共生?地方社区如何主导或参与生态目标的设定?国家层级的政策如何落实到村民的日常决定中?

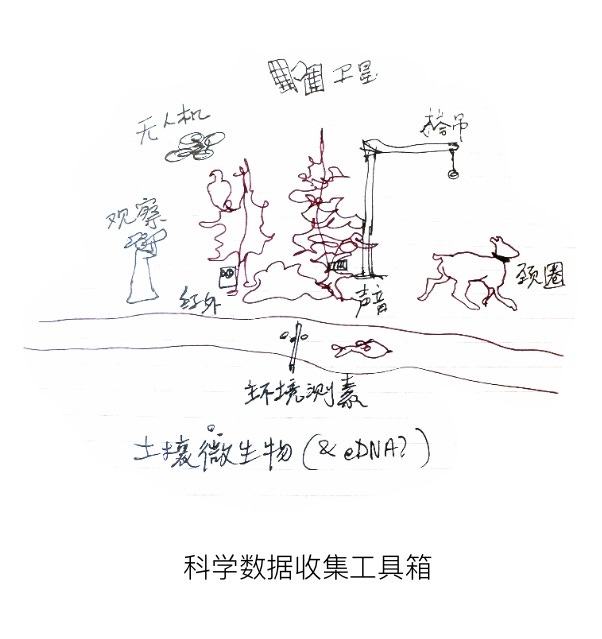

图8 我们目前的生态数据收集手段包括:观察记录、无人机拍摄、遥感卫星、塔式观测、声音监测、标记追踪、环境DNA、水质和微生物分析等。