Last week, I focused on nonfiction comics: how oral history and community stories can be told visually in a way that is accountable to the people sharing them.

I talked with artists and conservationists, revisited my own projects, and gathered tools for turning interviews and lived experiences into comics.

Structure: From Conversation to Comic

I’ve been interested in comic as medium of vulnerable and powerful stories since 2023. This week I visited two comic artists: Anusman and Erteng. They taught me how to build comics from interviews and daily conversations.

Anusman creates comics based on everyday people. At his exhibition, elders featured in his book came, ate buns, and chatted.

The project that stood out to me was his book for "The Lullaby Project" in Beijing, where he revisited the elders who sang lullabies, listened to their stories, and made really nuanced daily life comics of their lives.

I was interested to learn what his process is for going from other people’s life histories to polished comics. He was kind to share. What he shared with a local elementary school gives the gist of how he works:

"I think it’s best if everyone can use a pen to document stories themselves. But many people may not know how to do it—what to do, what to ask, how to get it onto paper. So let me share one method. It’s not the only way.

[Earlier, a child shared a lullaby her grandmother sang to her, called 'Cross-Leg Toe Tap.' Everyone sits cross-legged on the heated brick bed. You sing a line and tap someone’s foot, then that person pulls their foot back. Each person has two feet. When the song ends, the person with the most feet still out loses.]

Let’s take this example. First, ask the grandmother if you can play the 'Cross-Leg Toe Tap' game again. Focus on playing—don’t stop to ask questions or take notes. Pay full attention to watching. How is the game played? Which foot is tapped first? How is the lullaby sung? What’s the melody? After playing it through once, then write it down from memory. If you forget parts, you can play again. But never interrupt or stop the game midway—that breaks the experience.

Next, draw what the people looked like while playing. Don’t use your phone to take pictures—observe with your own eyes. Only through observing and drawing can you capture the necessary details.

Then, ask the grandmother about her childhood. What was it like? How did they play this game? Did her own grandmother tell her stories? What was life like then? Ask as much as you can, and write it all down by hand—don’t rely on recording or photos.

The final step is to organize everything. Sequence the events, and weave the materials together into a story."

After our discussion I understood that my main obstacle is structure: to face the massive amount of materials and synthesize them into a story that others can also understand, feel, retell.

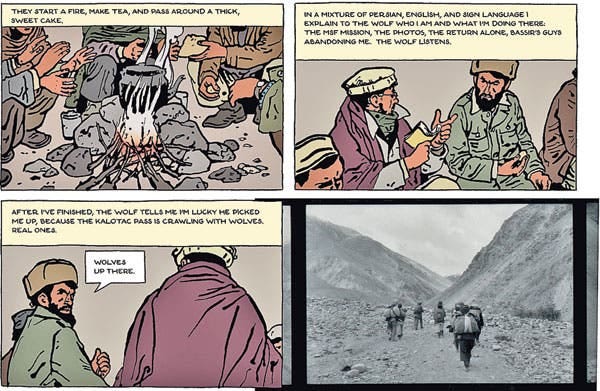

The structuring decisions include when to use drawing as opposed to writing, photo, audio, or other media. Comic is slow like writing so it holds a different power from photos and videos. There are memories, thoughts and emotions that are hard to capture with words or photos so comic has the unique role to fill in the gaps.

He reminded me that the structure step comes after fieldwork. When I go to Zoige Marsh (my fieldsite in July), I can talk, observe, draw, record, and write. Later, I can review materials, choose one narrative thread, and refine it with help from people like him, and inspirations from comics like “The Photographer”.

Erteng, the second artist, reinforces this with his teaching. He runs a traditional chinese drawing class for children. A recent homework was:

Observe your own hand

Write 50-100 words about it

Sketch a draft

Refine the sketch

Ink the final version

His 8-12 year old students helped me think about how to turn sentences into images. One told me, "If your sentence says, 'My hand is darker than Yanyan's,' then just draw one hand up and one down, and paint one hand totally ink dark!" The kids teach me I can be a lot more straight-forward and funny in my drawing.

Steps to make comics from oral stories:

Collect: Spend time with people. Talk. Listen. Take notes. Draw. Record only when appropriate. Visit archives or museums if relevant.

Structure: Choose a focus. Organize the story. Discard what doesn't fit.

Sketch: Start with fragments. Draw rough drafts.

Finish: Iterate. Work with editors if making a book.

Service: what stories need telling?

I also spoke with conservationists working in Tibetan villages like Sayong and Nanren. Sayong recently relocated from the mountain down to the river due to ecological redlining. Nanren is trying to stay in the mountains by developing new income sources like eco-tourism, local products, and conservation programs.

Before speaking with them, I spent a few days reading and listening to articles by Cicheng, a local writer from Sayong. He writes concretely about personal experiences, village legends, and ecological changes. One story that stood out described "Lu," a sacred tree spirit. To move a household or cut a Lu tree, villagers must invite a ritual specialist to transfer the spirit using a five-colored thread tied between the old and new trees. If this fails, they would feel physical pain and soreness in their own limbs when they chop the tree. This is a sign that the spirit hasn’t yet moved. These stories hold both cultural and ecological meaning.

The conservation staff told me that while they see Lu as ecological tradition, government oversight in the region treats anything remotely religious as sensitive. They warned that any story involving belief systems might be censored or require review. This tension between telling community stories and navigating censorship is something I need to consider carefully.

When I asked what kinds of stories would actually serve their needs, the team focused on three areas:

1. Drawing Together

First, they really liked the idea of having local kids draw together to produce their own perspectives. That’s something I had been enjoying intuitively in different places. When I draw alone, kids and elders naturally want to join, or ask questions, or bring in leaves, flowers, burnt tree branches. Drawing becomes a shared activity. The team said they hope to try something like that when the kids return for summer break.

2. Livelihood

They were interested in how comics or other media could support livelihood: through tourism, mountain tours, local products, conservation fundraising. I still hold questions about why tourism is expected to fill the role of sustaining communities when the economy is struggling and there could be subsidies. But it’s clear they want stories that show how people care for land and how that care could support income too.

3. Authorship

They emphasized that young people in the villages should decide what stories to tell and what direction to take. Sayong is not as focused on tourism as Nanren, but is located in a conservation zone for endangered species. A lot of the youth are now in college, and some do want to stay near their ancestral land while remaining economically sustained.

My Next Steps

I hope to keep practicing and improving on the clarity and reciprocity aspects. Many people told me my comics feel lively but unfinished. I agree. I want to keep the liveliness but improve the structure and clarity. I want to be better at completing stories so others can understand and connect with them.

And when I am in Zoige in July, I will focus on openly listening, observing, and sketching.

Lastly, throughout the week, while learning from others’ comics and community stories, I enjoyed compiling exercises from past experiences where I drew and wrote with or for others. It felt good to recognize that this practice is meaningful to me and might also be useful to others.

Further Reading

Nonfiction comic recs from Guilingongyuan: they categorize into comics about story from self, others. There is the history of the Vietnam war nonfiction movement. The recentering of nonfiction doesn’t mean there is no fiction, rather there requires research, interviews, artifacts. Comic is often very private in the expression and storytelling, but to center on real stories mean to be present.

Oral history resources: Voice of Witness (recommended by Shenghan), Robert Karl applied history reading list

From the FoodThink bookshelf: Soil zen (让梦想扎根 page 68-88)

From the Inner Mongolia translation group: The animalification of nationalist sentiments: horse, herder and homeland relations in the construction of nationalism in Mongolia

中文

上周,我专注于非虚构漫画:探索如何以视觉方式讲述口述历史和社区故事,并对分享故事的人保持责任感。

我与艺术家和生态保护者交流,回顾了自己的项目,整理出一些将访谈和生活经验转化为漫画的工具。

结构:从对话到漫画

自 2023 年以来,我就对漫画作为一个讲述脆弱又强大故事的媒介感兴趣。本周我拜访了两位漫画艺术家:Anusman 和 二藤。他们教我如何从日常对话和访谈中构建漫画。

Anusman 创作的漫画取材于普通人的生活。他的展览上,书中的老人亲自到场,吃包子、聊天。

最令我印象深刻的是他在北京参与的“寻谣记(The Lullaby Project)”项目。他重新拜访了唱摇篮曲的老人,倾听他们的故事,创作出细腻描绘日常的生活漫画。

我很好奇他如何把他人的人生历史转化为成熟的漫画作品。他很乐意分享。他曾在本地小学中分享了他的创作方法,大致如下:

我想大家如果能自己用笔记录故事就最好了,但大家可能不知道具体该怎么操作,该做什么,问什么问题,如何落到纸面,我来说一个方法,不一定是唯一的。

【前面有一位小朋友说了一个奶奶给她唱的童谣,叫盘腿捻,做法是大家盘腿在炕上,然后唱一句点一个人的脚,点完就缩回去,一人有两支脚,童谣唱完,谁的脚剩的最多,谁就输了】

以这位小朋友刚刚讲的为例,我们应该先和奶奶说,奶奶我们能否再玩一次盘腿捻,这里专心的玩,不要说玩一下就停下问问题,记录。所有注意力都要集中在观看上,看游戏怎么做,先点哪里,童谣怎么唱的,什么曲调的。完整玩完一次,再去记录,凭着记忆去记。如果没记住可以再玩一次。但千万不要在游戏中途打扰和停止。这样童谣游戏就不完整了。

接着,去绘制玩的人的样子,不要用手机去拍,要自己观察,因为只有观察和记录才能记下需要的细节。

再之后去问奶奶,她小时候是什么样子的,怎么玩的,她的奶奶给她讲了什么故事吗。当时是什么样子的。等等,能有多少就记多少,同样也是用笔去记,不用录音和拍照。

最后一步,整合前面的内容,开始编故事的顺序,将上面的内容融合到一起。

通过我们的对话,我意识到我目前面临的主要障碍是“结构”:如何面对海量材料并提炼出一个能被他人理解、感受、转述的故事。

结构上的选择还包括何时使用绘画而不是文字、照片、音频或其他媒介。漫画和写作一样是“慢”的媒介,它具备不同于照片和视频的力量。有些记忆、思绪与情感很难用文字或影像捕捉,漫画恰好能填补这些空白。

他提醒我:结构是田野之后的事。我在 7 月去若尔盖湿地田调时,可以先说话、观察、画画、记录、写作。回来后再回顾资料,选择一个叙事线,借助像他这样的人和一些漫画作品(如《摄影师》)来精炼它。

第二位艺术家“二藤”,在教学中进一步印证了这一过程。他为儿童开设了传统中国画课程。最近的一次作业如下:

观察自己的手

写 50-100 字的描述

起草草图

精修草图

上墨完成

他那些 8-12 岁的学生让我思考如何将句子转化为图像。一个孩子告诉我:“如果你写‘我的手比燕燕的手黑’,那你就画一只手在上、一只手在下,然后把其中一只画得黑乎乎的就行了!”这些孩子让我明白,画画其实可以更直接、更有趣。

如何将口述故事变成漫画:

收集: 花时间与人相处。交谈、倾听、笔记、绘画。适时录音。如有需要,访问档案馆或博物馆。

结构: 选定重点,组织故事,舍弃无关内容。

草图: 从碎片开始,起草粗略图画。

完成: 多次修改。如果是出版书籍,可与编辑协作。

服务: 什么样的故事是需要被讲述的?

我还与一些在藏区村庄(如萨勇、南仁)工作的生态保护者进行了交流。萨勇因生态红线的规定从山上搬迁至河边,而南仁则努力通过生态旅游、山货、保护项目等方式留在原地。

在和他们交谈之前,我花了几天时间阅读和聆听了本地作家此称的文章。他具体描述了个人经历、村庄传说与生态变化。其中有一篇讲“Lu 树神”的故事令人印象深刻:若要迁家或砍伐 Lu 树,村民必须请来仪式师,通过五色线将树神从旧树引到新树。如果仪式失败,村民在砍树时会感觉自己四肢酸痛,这是树神尚未迁移的信号。这些故事承载着文化和生态双重意义。

保护工作人员告诉我,他们将“Lu”视为生态传统,但政府将所有与宗教信仰有关的内容视为敏感,可能会被审查。他们提醒我,讲述社区故事时要认真权衡信仰内容与审查的张力。

当我询问他们最需要怎样的故事时,团队提到三点:

1. 一起画画

他们非常喜欢让本地孩子们一起画画的想法。这正是我在多个地方直觉上也在做的事。当我独自画画时,孩子和老人会主动加入、提问,或拿来树叶、花朵、烧过的木枝等参与。画画变成了一个共享活动。团队表示希望暑假孩子们回来时能尝试类似的活动。

2. 生计支持

他们关心如何通过漫画或其他媒介支持生计发展:如旅游、山地导览、本地产品、生态筹资等。我仍然有疑问:为何旅游被视为社区可持续的主力方式?当经济困顿时,是否也该有补贴?但显然,他们希望故事能展示人们对土地的照料,以及这种照料如何可能转化为收入。

3. 作者权属

他们强调,村里的年轻人应该决定要讲什么故事、走什么方向。萨勇不像南仁那样注重旅游,但位于濒危物种保护区内。许多年轻人已在大学就读,有些希望今后能在祖地附近生活并获得经济保障。

我的下一步

我希望继续练习“清晰表达”和“互惠”的能力。许多人说我的漫画“有生命力,但不完整”——我同意。我希望保持活力,但提升结构与清晰度。我想更好地完成故事,以便让更多人理解和产生共鸣。

7 月我将在若尔盖,重点将放在聆听、观察与绘画。

这一周,学习他人漫画与社区故事的同时,我也整理出以往自己与他人共绘、共写的练习。这让我意识到,这种实践对我有意义,也可能对他人有用。

延伸阅读

来自桂林公园的非虚构漫画推荐:他们将漫画分为“讲述自我”与“讲述他人”的两类。提到了越战期间非虚构漫画的兴起。非虚构的重心并不排斥虚构,而是要求调研、访谈与资料搜集。漫画常常非常私密,但若想讲真实的故事,就必须“在场”。

口述史资源:Voice of Witness (盛寒推荐)、罗伯特·卡尔加收的应用历史阅读书单

食通社书架:《土地禅》(《让梦想扎根》第68-88页)

内蒙古翻译小组:《民族主义情感的动物化:马、牧人与家园关系在蒙古国民族主义建构中的作用》

weeeee i loved this!! so much care so much wisdom